Toxic Yuri Aufhebung

My brunchmate does not understand Buddhism. It is the middle of the month of March, he is twice my age, and he once told me about his attempts to take two classes on Buddhism in one semester. In the end, he did not write the final paper for either of the classes, simply because he could not wrap his head around the concept at all. This is my brunchmate with whom I am talking about how I am, just a little bit, insane.

I do have decorum; it was reasonable in context. He had first been telling me about how he experienced loss, as a perpetual frustration that a certain object which should be there was not there. He explained that in his head, every object he had ever emotionally invested in was always present, and should have a correlate in the real world. When he could not find these correlates, he would become frustrated, like a perpetual thorn was in his side. So I wanted to explain what my experience with the absence of objects was, which led me to dissociation.

I experience quite a lot of jamais vu. Jamais vu is the underappreciated sister of déjà vu and presque vu (i.e. when something is on the tip of your tongue). Where déjà vu takes the object in question and doubles it, and presque vu takes it and makes it come up just a bit short, jamais vu removes it entirely. When you experience jamais vu, you can look at someone or something you’ve known for your entire life and feel that you’ve never ever seen it before. In fact, when it happens to me, it usually affects everything I look at and see. I feel that I have never thought before, I have never experienced before, let alone formed relationships with any of the things that I am seeing. I still retain all my memories, but I also feel that I’ve never remembered before, and so the faculty of memory becomes inherently untrustworthy, like having been handed a cache of information which is totally foreign to me. I was explaining that, in these moments, I know how to reassure myself enough to wait for them to pass. But if I did not, they would be scary enough to make me paranoid.

I don’t know how much I elaborated, though I very well could have done so. I could have, and might have, talked about being a kid, when I became fixated on establishing the continuity of my experiences. It became important to me to mark out specific moments in which I was conscious of being conscious, so that when I had a moment of jamais vu, I could look back at that moment and say that I was there. But the method never entirely worked, because it could not establish that the same consciousness was there; only that a consciousness was there. And I also could have talked about my parallel experience of terror at the concept of death, due to the great nothing of non-perception I could feel very very strongly. As a child I was acutely aware of that space outside my vision, the darkness beyond my eyes and my perception more broadly, where things were but where consciousness of any sort was imperceptible. But I did not take this in a spirit of solipsism. Instead, I felt that in some sense death had already essentially won—that I was clinging to sand, and that if I simply let go of this little illusion of a patch of light, being itself would pass away. It would really not be so difficult to just let go.

In any case, the impression it left on him was that he said, “It sounds like you could very easily be a Buddhist.” And Heaven knows he is not the authority on accurately characterizing Buddhism. But I understood it—the sense of non-self, of anattman, and of the ability to detach from everything. What was funny to me was that that is so different from the philosophy I’ve actually adopted. I believe, with Spinoza, that desire is the very essence of a being and joy the increase of being, and with Traherne, that loving attachment to all things is the vocation of human beings. I believe in the cause of atman’s continual desirous striving, even as the core of my being feels empty. I am a hollow who believes in yearning.

I swear this post, for once, is not about God. This post is about yuri.

I have a friend who does not understand “me.” Rather, she does not understand what I mean by “me”; she understands what she means by “me.” “If you take me away and put me alone, I am still me,” she says, “I never lose who ‘me’ is.” Meanwhile, I lose myself constantly, depending on who you take away. I confess my total dependence, that I have offloaded parts of myself to others, and that if these others are taken away, I find myself exiled from my self. My friend does not understand this. “Usually I find that when people perceive me, they perceive what they want to see, not what I am.” And I agree; many people do have poor-quality perceptions of me which I would be foolish to rely on. But often I am one of them.

I identify to some extent with Lacan’s description of the mirror phase. In the mirror phase, an infant is confronted with their image, which they recognize to be themself. But they find there to be a fundamental incongruity between their mirror image and themself. Their mirror self is a definite object, discrete and coherent; but they do not experience themself as discrete or coherent. Instead they are a jangle of abrupt movements, of clumsinesses and failures, essentially incoherent and put to shame by the coherence of their own image. That is precisely how I feel about myself when I am on my own, separated from my trusted and coherent images stored in the minds of others. I am given over to strange impulses with no respect for self-image, carried on by random and severe melancholies and obsessions, given up to other powers against my will. My life appears to me as a history of clumsy and disastrous possessions, of spontaneous lines of flight. It does not actually appear as much of a life at all, because none of these instants tie together. It is instead in the mind of others that all these moments appear coherent, that they seem to come together in their heads as being of a single object, allowing me to say of myself, with relief—“Ah, I see! I’m Lilli!” Notably not the name I usually introduce myself with—“That would be Lillian”—but the nickname I am most frequently called by people who know me. I don’t present Lillian to them; I receive Lilli.

You might laugh, but more so than Lacan, what it makes me think of is Irigaray. Irigaray argues that while the phallus is intrinsically visible and unified, and thus conducive to a logic of settled identity, the vulva-vagina-etc. complex of organs are not intrinsically unified or even visible, being seen comprehensively through the mirror of the speculum or else not seen at all. The idea that there even is one central libidinal organ, and what organ that is, has to be taken on faith. That is basically how I feel when I am left unobserved. It’s not that I feel plural, like I have several states and a shifting identity, but that the whole status of identity drops out and recedes and is replaced by a multitude of impulses which drive me any which way, whatever I’d like, not without a continuing interior dynamic but not a dynamic of coherence per se. Further, as another layer, this dynamic is accompanied by shame: by a sense that whatever is happening is basically disordered. It’s not hard to convince me that there is something wrong with me. As much as I do not believe anatomy is destiny, I’m not sure I appreciated this argument as much before reaching the, “I have no idea what’s going on inside my body and I’m reliant on my (male) doctors to tell me” phase of my life.

As much as it all sounds like pseudo-intellectual garbage, it really does describe how I feel. I am an entity of partial objects, operating in flows and not by settled states. What I feel like my loved ones give to me, which I lose if they are not present, is at best an opportunity to miraculate those functions onto a stable body, one which is nevertheless not of those objects, one which even repels those objects. My loved ones know me as a body, which interrupts my experience of myself as a process; yet that body is produced through the process that it interrupts, and so the process seems to emanate from the body. There are better bodies to be miraculated on than others: there are bodies of lack, bodies which ruin me; and there are bodies which bring me into effect. But without a body at all, embodied existence simply recedes, and whatever the current project called Lillian is begins to operate in darkness. You will not see it happen, because you cannot see it happen. You will have to take it on faith that this is what happens.

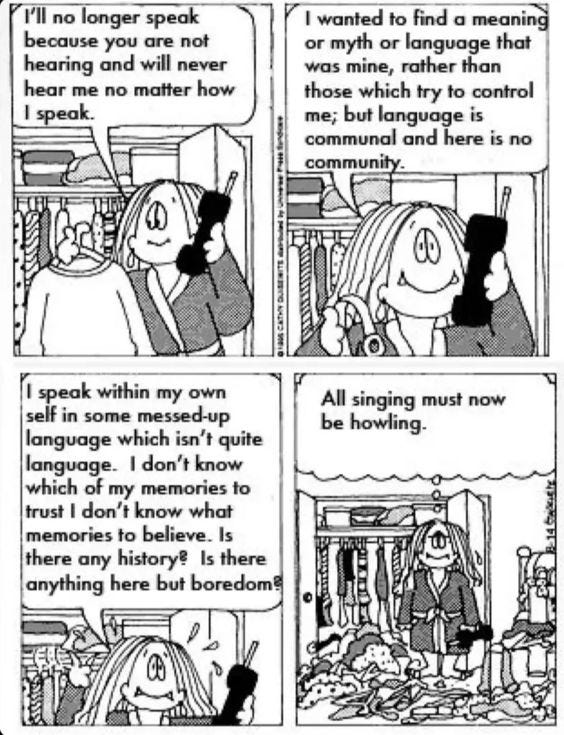

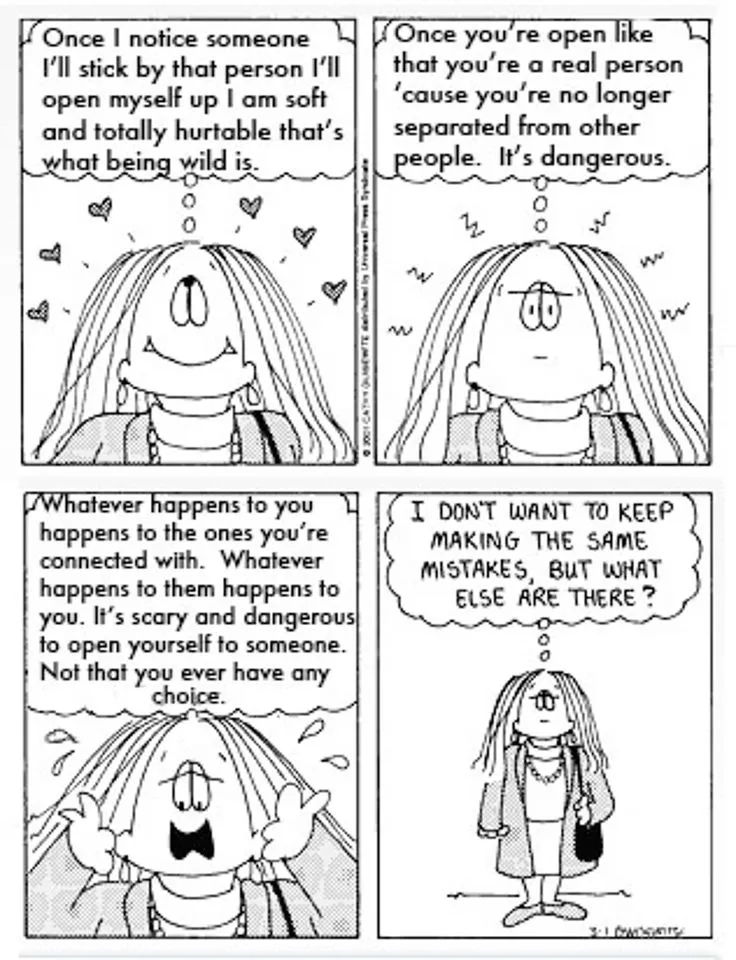

At least one other person gets it. Apparently it’s from a deleted Tumblr blog which matched Cathy comics to quotes from Kathy Acker books... I’ll take kinship wherever I can get it.

People are talking about toxic yuri. Everybody nowadays loves toxic yuri. I myself hate toxic yuri, but that is only because I love it. I think the first time I was conscious of liking something like “toxic yuri” was when, when I was 14 or 15, I read the webcomic Dumbing of Age on a daily basis for a couple of years. I was right at the beginning of my transition, and I was also in the middle of my teenaged depression and despair. And in Dumbing of Age, at the time that I was reading it, there was this couple that was very much toxic yuri. Both girls were alcoholics, and both were depressed, and one was quite cruel to the other to start with, and the relationship itself was an abuse of power since one was the other’s TA. First they began by trying to fix each other; then they bonded over their failure to fix each other and began to talk about committing suicide together. This hooked me. This was exactly what I wanted to see. I essentially read the comic for no other reason than to watch two girls destroy each other.

Attached, an image of the girls I thought were epic, around as far as I got into the comic. (Apparently? the girls stopped doing toxic yuri shortly afterward, so I stopped reading.)

The other case, of course, was Madoka Magica. I didn’t originally like Madoka for its “yuri” elements, if you can really speak of those. I adored the witches constructing labyrinths out of their broken aspirations, the descents of the magical girls into despair, the wishes which tried to break out of what seems to be an inexorable curse, and the obsessive drive which led a girl to Groundhog Day herself out of doomed conviction. But I think I always recognized that there was a female homoeroticism which is inseparable from all these elements, and eventually, spurred on by my best friend who saw certain analogues between Madoka and real life persons, the “yuri” elements did come to the forefront of my engagement with the show. I think the seed of that investment was always there, it just needed to be actualized.

I’ll raise one other case of doomed yuri, one I actually don’t have much personal engagement with, but which led me to write this post. In the horror game Fear & Hunger 2: Termina, there are two girls who hail from an alternate black magic polytheistic Vatican City: Marina and Samarie. Marina is a trans girl, and Samarie is her deeply-obsessed lesbian stalker who has never even spoken to her before the game. Samarie is also a child subject of horrible tortures in service of dark gods which have dramatically shortened her lifespan and left her, quite understandably, wrecked. Samarie is notable for killing Marina’s father and for potentially transforming into a deformed and powerful enemy called Dysmorphia while crying out, “Abomination!? I’m absolutely radiating! LOOK AT ME!! YOU CALL ME AN ABOMINATION!?” The ship of Samarie and Marina is termed “toxic yuri" by its fans, and is so similar to the Madoka/Homura ship that there are several pieces of crossover art. This one is the first image that shows up when you search up “Marina and Samarie”, and is tagged “Cannibalismcore Love.”

I think these three examples sum up exactly what my investment in toxic yuri has been in over the years. The basic toxic yuri dynamic which is compelling to me is one in which the characters are fundamentally and primarily disordered. Madoka Magica is a great example, in that it’s often approached as a yuri show while having essentially no real romantic content, just a continuous sequence of despair and suffering. Fear & Hunger 2 operates the same way: while there is expressed romantic interest, that interest is hopeless and completely unfulfilled, while the actual context is one of horror and death. My first toxic yuri investment, Dumbing of Age, has a lot more fulfillment, but it is also clear that the relationship has no future and no hope and is awful for all parties involved. The basic state is not a romantic relationship deformed by toxicity, but a toxic manner of life practiced by girls or women whose latent homoeroticism is readily apprehended by the reader.

My first reason for investment in toxic yuri of this kind is that I relate to the feeling of having a habitus which is incoherent and apparently disordered, not suited to the kind of stable meaning-construction which a “proper” life is supposed to imply. The second reason is that, in these sorts of cases, it is clear that the establishment of the relationship will not fix the incoherent manner of life. It is vitally important to the fantasy that toxic yuri will not pretend to fix you. Toxic yuri does not map the incoherent impulses and desires of the girls in question onto any sort of viable body, and instead intensifies them to a torturous intensity. Because toxic yuri will make you worse, it is not a fantasy in which one is given one’s identity by another. It is instead a fantasy in which it is possible for two people to exist together in what is normally a private state of derangement. Toxic yuri is a “folie à deux,” being insane together.

Toxic yuri is also not a mere fantasy. I have gotten this dynamic I’ve pined after before, twice in the form of an actual codified romantic relationship, and then at least twice more as non-romantic relationships with strong homoerotic undertones. Each of them, let me be clear, left me a complete wreck afterward. None of these situations had the rudiments required to succeed. But that’s part of what made them precious: it’s not a “folie à deux” without the “folie.” If they were set up to work, they wouldn’t have the kind of insanity which causes them to be so precious, they wouldn’t fulfill the urge which is so essential to the dynamic to begin with. Toxic yuri is a kind of psychosis-adjacent lesbian separatism, women among themselves outside the realm of reality. It suspends the kind of phallogocentric logic of identity which is required to exist viably within the world, and so it never works viably within the world. Toxic yuri always takes place in the witch’s labyrinth, where space warps and time turns back on itself to make desire which is not possible actual.

Okay, I hear you say: you’ve fulfilled two thirds of your title, but what about the last word, Aufhebung? You seem to be promising something like a dialectic of toxic yuri, and you haven’t provided it yet—so where is it? Well... to be honest, I’m not entirely sure I’ve got this dialectic in working order. But I’ll give you what I have.

In a dialectic situation as I understand it, we begin with the image of an abstract situation. This abstract then meets its negation in another image latent within the first situation, which seems to cancel the situation which it is itself conceived in by contradicting its image. Having moved from this first abstract image to this negative image which is contained within it, the dialectic motion attempts at first to return to the abstract, but finds that it cannot do so, and so ends up crossing to a new concrete situation which at once cancels both the abstract and the negation while in some way preserving both of them in a transformed state within the new situation.

In the case of toxic yuri, the abstract and the negation are readily apparent. The situation in question is one which, from the perspective of the abstract idea, is fundamentally disordered. The situation portrayed by toxic yuri is essentially and self-consciously non-viable, diagnosed as pathological by a rational gaze. In the abstract, toxic yuri is interpreted as a case of death drive, two people’s spiralling into mutual self-destruction which foregos healthy pleasure in favour of a jouissance which is at once ecstatic and excruciating. However, in crossing over from the abstract to the negative, this anerotic thanatos ends up supplanting eros as a superior form of eros. Within the situation of toxic yuri, the negative image portrays the radical togetherness of the girls in their spiral toward destruction as such a peak of erotic satisfaction and of passionate love that no alternative is satisfactory. In fact, toxic yuri becomes the only healthy or desirable relationship dynamic, the only one that is viable—certainly, the only one that could be viable for a type of creature, a type of girl, which is so deranged and unhinged. In the negative image, “all is dross that is not Helena” from Marlowe’s Faustus; coincidentally, HELENA = AQ 99 = MADOKA.

Let’s consider specifically the case of Madoka Magica. The immediate, abstract, pathologizing view is to say that Homura’s love for Madoka is completely non-viable and unhealthy. It is an affection which cannot be mutual due to irreconcilably bad circumstances. It is obviously stalkerish and emotionally stunted; it is not a mature eros, it is an all-consuming drive. The abstract image accurately perceives that Madoka Magica is not a yuri anime, that it is a tragic anime about despair and death. But the negative image rejects these value judgements. In portraying Madoka Magica as a yuri anime, as in e.g. yuri fanart or headcanons of the two characters, it perceives in the tragic situation a far more adequate content of intimacy than is possible in healthy, stable situations. Although happy slice-of-life-esque fanworks may seem to depart radically from the show itself, the negative image is still of the same situation as the abstract image; it simply sees within that situation exactly what the abstract image cannot see.

Because the abstract and negative images exist within the same situation, they are not entirely separate from each other. Rather than precisely two possibilities, they encompass a continuum of possible representations between the two dialectic poles. For example, fanart which re-presents Madoka Magica, or other cases of toxic yuri, as contented stories of wholesome affection borrow their concepts of health from the abstract while maintaining an obvious investment in the negative. On the other hand, depictions which stress the cruel agony of the romantic encounter’s non-viability, while agreeing with the abstract diagnosis of the situation as disordered, continue to derive enjoyment from the negative’s depiction of eros under the aspect of cruelty. In fact, swearing off toxic yuri entirely, either in favour of a commitment to “good representation” or to disillusioned cynicism, are not extremes, and are still bound up between the abstract and negative intuitions and have not truly moved beyond them. A turn toward good representation must still take its categories of “goodness” from the abstract and of “desirability” from the negation; a turn toward cynicism recalls the heights of the negation with pain because it remembers the diagnosis of the abstract.

None of these cases represent a Toxic Yuri Aufhebung™. To have that, we must move out of the negation without returning to the abstract, abolishing the present situation entirely while also gathering it up into a new concrete situation. Each of these cases, however, merely bounce between the negation and the abstract, trapped in such-and-such a year of the Toxic Yuri Era. It is not easy to pass simply between situations in such matters, because, as opposed to the idealities with which Hegel works, toxic yuri is in fact a historical situation, a specific situation in contemporary economies of representation and of homoerotic desire, bound up in the enculturations and technologies which make toxic yuri as we today know it possible. By thought alone, the best we’ll ever get to is a Provisional Notes on a Toxic Yuri Aufhebung. Perhaps that would have been a more honest title.

Before we get on to the question of what it might look like to transcend toxic yuri, we have to ask why we might want to turn away from this situation. For this question I can only turn to my favourite writer on romance: CCRU-era blogger undercurrent, in the comments section of k-punk. My adoration for these particular blog comments may strike you as abnormal, but somehow, in their assault on Mark Fisher’s misogynist representation of women as wildlife, undercurrent somehow manages to make my all-time favourite critique of “romance”:

>The whole thing was very romantic.

Yes, romanticism is the enemy because it is precisely the abdication of thought and change for comforting nostalgia and wistfulness; or giving up on the (difficult) possibility of loving a person for being aroused by the impossibility of an image. A romantic encounter is not a joyful encounter. In fact I’d say it’s constitutive of romantic encounters that even when they seem to be sweeping and cosmic they are about subjective-shutdown-disconnection not connection.

In thrall... precisely why it’s categorised as bad affect, something to be escaped—the febrile theoretisation is just a extra reflexive level to the capture. Fascination becomes addiction, and whilst the Velvet Underground are fine in small doses, there’s nothing essentially interesting in listening to a heroin addict talking about how nice it feels if they simply persist in wallowing in their slavery. Obviously if romanticism is your thing then you’ve made a lifestyle choice: but it makes for a monotonous closed-circuit eroticism which is imaginary and solitary, but whose media-virulence has corrosive effects in the reality of people’s (lack of) connections with each other.

My fundamental reason for wanting an end of toxic yuri is the same as wanting an end of capitalism: I’d like better for the girls. Toxic yuri can appropriately be termed a kind of romanticism, of the kind that undercurrent rails against. Though it is itself a situation, the situation of that situation is that of “the reality of people’s (lack of) connections with each other.” The kind of “being women among women outside the logic of normal identity” which toxic yuri yearns after it attains fantastically, because its real attainment in this world is more or less unthinkable. By this world, I mean the world as it is represented in the ideology of the abstract, which is an ideology of condemnation and disorder in which the possibility of a folie à deux is foreclosed. Because that ideology has the ruling position, the desire for folie à deux flees to the ideology of the negative, which valorizes the disorder that the abstract diagnoses as an erotic condition. But fundamentally, this is still a moment of “being aroused by the impossibility of an image.” The eros within the situation marked as “disordered” is not experienced directly, and is instead mediated through arousal at the idea of being disordered. Toxic yuri consequently becomes narcissistic, and based on the exact kind of logic of stable identity which it seeks to subvert, preferring the idea of what it is to the tactile dynamics of the encounter.

I do not want to advocate for the abstract. I have tried for the abstract as well as the negation, and have found myself unable to actually return to the abstract from the negation, even as I am also unable to cross out of both into the new concrete situation. The effective claim of the negative image is that, having attained the eros of mutual homoerotic self-destruction, no other will suffice. The consequence of this claim is a curse, to be loved either impossibly or not nearly enough, and in the end, possibly both. I have no particular dislike for the negative; I prefer the values of the negative to the abstract if I’m being honest. I love what the negative lays claim to. I am partisan to its immanent intensity, the anti-identitarian flux which I feel is my natural state of being, only shared, no longer alone, and so in some sense no longer tragic and deformed. That is a cause which is worthy and noble and which I deeply desire. However, I find the negation, being bound up with the abstract, deeply inadequate to champion that intensity.

As much as I’ve played around, with various degrees of irony, with all these identities, I do not want to be an assimilationist gay, and I also do not want to be Homura and Madoka. I do not want to be a jaded femcel, I do not want to be sworn to celibacy, I do not want to be a Halimede-esque chaser, I don’t want to be a neo-lezsep or a political lesbian or politically t4t, I do not want to be a political heterosexual, I do not want to be any of it! I do not want to be anything within the continuum of the abstract and the negation of the situation of homopessimism, which is my more serious way of referring to the situation of toxic yuri. In fact, I do not want to be. That’s the point! That’s the whole point! I want... I want... I want to want, I want to want and want and want. I want...

Abba Lot went to see Abba Joseph and said to him: ‘Abba, as much as I’m able, I say my little office, I fast a little, I pray and meditate, I live in peace, and as much as I’m able, I purify my thoughts. What else can I do?’ Then the elder stood up and stretched his hands towards heaven. His fingers became like ten lamps of fire and he said to him: ‘If you want, you can become all flame.’

I want to become all flame. But I want to do it with someone, as one flesh—one flesh without a body, turning into ten lamps of fire together, into a decimal labyrinth together. I want the thing the negation is saying it will sell me but hasn’t yet. I want the Way—but the Way that can be walked is not the eternal Way, and the name that can be named is not the eternal name. I want what what’s in, with, and under toxic yuri, not just for me but for all the brainfucked tgirls who care about this stuff out of our variable states of insanity. But I have no idea where to find it!

So here’s where I have to deliver. Where is the Toxic Yuri Aufhebung? How do we get there? Well—I don’t know. I have no idea if there even is one. And the only people who seem to really want it are the people who hate dialectics, understandably in this case, because overturning the logic of identity which keeps the desire at the heart of homopessimism locked up would seem to abolish the whole system of abstracts and negations altogether. I’ve essentially argued myself right back to what, after my first great toxic yuri relationship succumbed to its impossibility in 2019, I identified as the solution: gender accelerationism. I think that what I’m talking about is, in fact, the libidinal context which makes it desirable to identify as G/ACC in the first place. What else do you think the “t4t’ circuit” is, other than the workings of this alt-economy of desire brought to unfathomable fruition?

So that’s my answer: just read Zeros + Ones by Sadie Plant and the works of Nyx Land with eros in mind and hopefully you’ll get what the answer might look like, as a dim apprehension of shleth hud dopesh, of “perhaps it can become so.” But I can provide, I hope, a few marginal notes, ones which may not be written otherwise. The first of these is from Thomas Traherne, in the Centuries of Meditations, from the 66th thesis of the second century:

When we dote upon the perfections and beauties of some one creature, we do not love that too much, but other things too little. Never was anything in this world loved too much, but many things have been loved in a false way: and all in too short a measure.

For the purposes of going beyond toxic yuri, the problem is, as the priest identified, not a defecit of intensity. The intensity always comes up too short; there is always room for more. The problem is falsity, clinging to the false and hedged-in image of what love looks like, which can never become fire as it ought to but can only smoulder. And the problem is also an over-reliance of love on a specific subject-object dynamic, which is always an identitarian formula and never a truly fulfilled folie à deux. Both of these problems are basically the same, being issues of false vision, substititions of an image (of the beloved, of the loving) for the actual project. The actual project is the cultivation of an intensity, the dark and babbling girlie derangement syndrome, in a context of genuine intimacy, no longer forced to be alone.

The second is to return to that phrase of undercurrent: “the (difficult) possibility of loving a person.” If the image of cultivating an intensity comes to replace the actual cultivation of that intensity, it becomes dramatically easier. In fact, the “femintensity” (to borrow k-punk’s word) to which I am referring can only ever be difficult to cultivate, because it is situated in a material context, that of toxic yuri, which is not at all conducive to its cultivation. It is difficult, also, for reasons of ethics, because if the other woman is not to be taken as an image-object she must be taken as a frontier of irreducible otherness which demands respect and not foreclosure, even if the borders of this otherness come to pass through one’s own self outside of stable identity. It must be loving, not in word and speech but in deed and in truth, and it must be loving a person, and not an image.

And finally, perhaps the most difficult item: a passage out of toxic yuri must be, in some sense, respectful to the abstract and to the negation it passes out from. It must take seriously the reason why it passed into the negation in the first place, rather than deny this passage through a kind of retroactive repression. Then it must take seriously the reason it passed out of the negation, recalling where the abstract was desirable or truthful over the negation to a degree that could not be ignored. And then, lastly, it must remember the basic impossibility of actually returning to the abstract, the ultimate non-viability of both poles for dwelling in. Fleeing Sodom and Gomorrah, it must know not to look back.

Simply thinking through this process will not work. It must be enacted, because toxic yuri is a

cierto mar, ay, de serpientes sueño yo.

Largas, transparentes, y en sus barrigas llevan

lo que puedan arrebatarle al amor.

That is to say, it is not an ideal, it is a sea of snakes with Hell in their digestion. And what I hope for in the end is a fire that is hotter than Hell’s.